Human Lens #136: 'The Boy and the Heron' Review

If this is Miyazaki's last film, boy is it a good one.

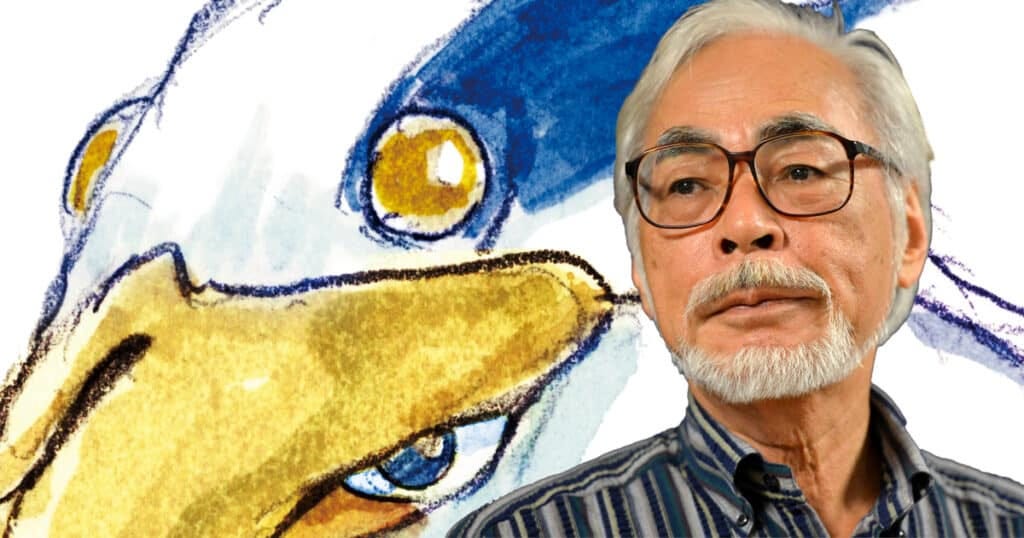

Hayao Miyazaki has a cynical outlook on the world. The world class Japanese animator, whose directorial portfolio rivals the likes of Scorsese and Spielberg, has been challenging audiences with innovations in animation for over 40 years. Now, at the age of 82, he has delivered his first film in 10 years, a second outing at a last film before retirement (and most likely not the last). While his films have garnered visuals and moments that have inspired and charmed multiple generations, their overarching themes are rooted in darker explorations and an inherent lack of belief within elements of humanity. The greatest example is his previous swan song, The Wind Rises — depicting the obsessive nature that the greatest artists put into their work and the destructive power that kind of life has. While The Wind Rises is a better suited, and more finely tuned, final chapter in Miyazaki’s filmography, his latest film’s personal touch and return to his quintessential knack of world building works as a more believable ending to a sensational career.

The Boy and the Heron, as international audiences know it, is a more profound and internal exploration than its adventurous and whimsical title may suggest. In this semi-autobiography near the end of WWII, Miyazaki is represented through Mahito, a young boy who yearns for his mother following her death in a hospital fire. Moving to the countryside with his father to live with his Aunt, whom his father has already married (with a baby on the way!), he discovers an odd looking heron has taken an interest in him, shadowing him around the property. In his depressive journey around his mother’s childhood home, the home of the Aunt he’s now being told to call mom, it’s understandable that a 12-year-old would grow malice towards his current situation — hurting himself to get his own way and feel in control.

It’s when Mahito finds a book, gifted to him by his late mother, that the emotional heartbeat of the upcoming journey takes root. The title of this book, ‘How Do You Live?’ is, in itself, a question that will follow our protagonist through the remaining runtime. But it’s also the title of Miyazaki’s favorite childhood book, as well as the title of The Boy and the Heron in Japan. While the title change is understandable to attract an international crowd, this original title serves the tone that Miyazaki was emitting better, as the adventure ahead, while whimsical and creative, is extremely depressing and introspective.

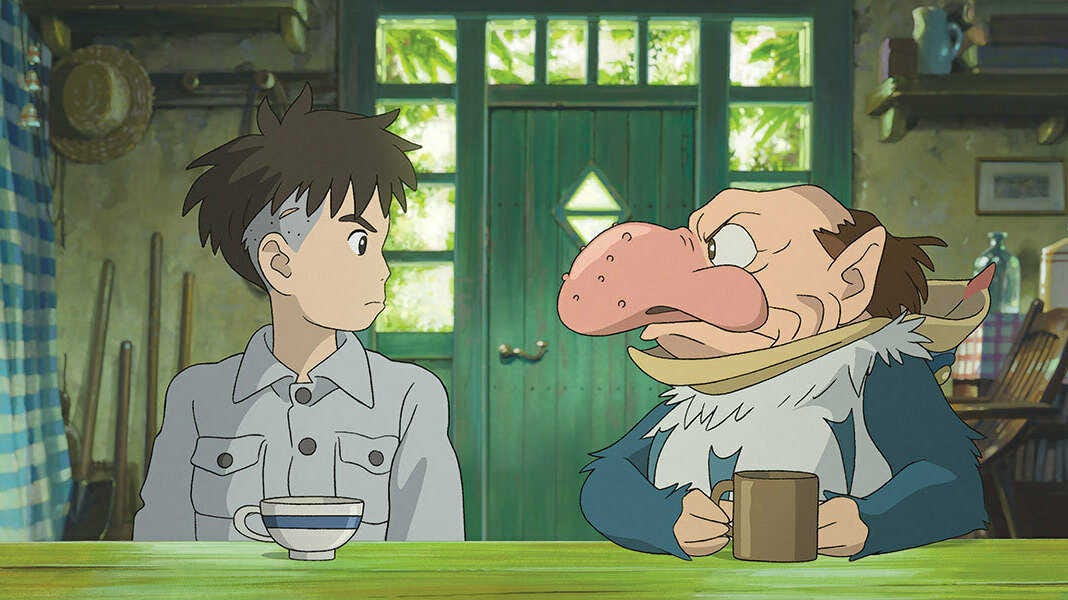

That doesn’t mean there aren't some fun and creative moments within the film, as that intriguing heron turns out to be a talking creature — portrayed in the English dub with an unrecognizably guttural vocal performance by Robert Pattinson. When his Aunt goes missing, Mahito is lured to a world between life and death by the heron, with that bird ultimately acting as his guide. This second portion of the movie feels completely different from the opening act, yet visualizes the complicated emotions and thoughts that are going through the head of Mahito.

With all this blathering about Miyazaki’s cynicism and nihilism, what he explores in this other realm is his most hopeful and retrospective. This world of adventure is a vessel for the filmmaker to play make believe, learning lessons and making amends with loved ones. Meeting a younger version of a Grandmother who helped at his Aunt’s house, Kiriko, Mahito learns of the nourishing aspect of those older than him, and the inspiring skills and experiences that they hold despite appearing weak in the eyes of a child. Mahito then has a run in with parakeets, a spiritual symbol to embrace our true colors, and a young girl with many similarities to his mother.

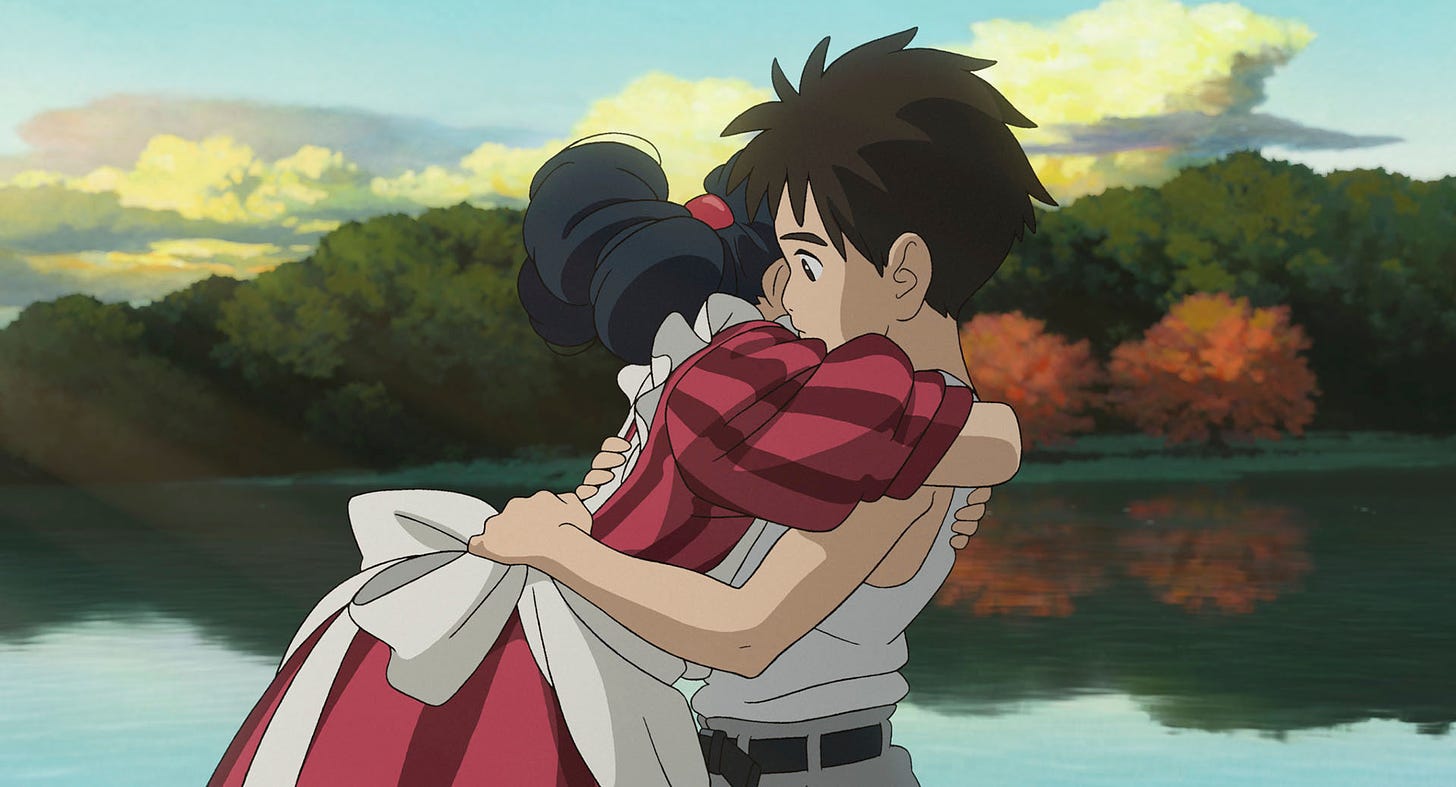

Matching themes with an earlier masterpiece from the animator’s career, My Neighbor Totoro, Miyazaki teaches us that the only thing we should be scared of is losing the people we love. This theme becomes most prominent in Mahito’s reunion with his young mother, and the acceptance he has that his Aunt is a loving mother to him as well. In the face of giant birds, wonky visions, and unmapped territory within an unknown realm, it’s the people that help Mahito through it and their connection to him that revitalizes his faith in the future. Although it’s a fantasy to reunite with the people we hold most dear, now long gone, it’s closer to truth than it is generated assumption that those people would be proud of us no matter who we have become. It’s this realization that leads Mahito to accept and admit the malice that was brewing in his heart, moving on to the next part of his life with a fresh perspective on the beauty of life.

If this is Miyazaki’s last film, then it’s a heartwarming goodbye to his audience and the people that meant the world to him. Not many people get to share what they want or should say with the people that shaped them into who they become. For Miyazaki, he is thanking his mentors for their generosity and guidance and penning an ode to his mother where, in reflection, he believes that she would be proud of him. We have a stronger effect on those around us than we believe, therefore our actions and relationships should refrain from malice as to constantly inspire, charm, and create. Malice is a wasted action and breeds emptiness that this man, whose cynical ideas have defined him well into his old age, is warning against. This is a final plea to not be inspired by Miyazaki’s career, but to be inspired by the world that you create for yourself. There’s nothing more powerful than a personal vision.